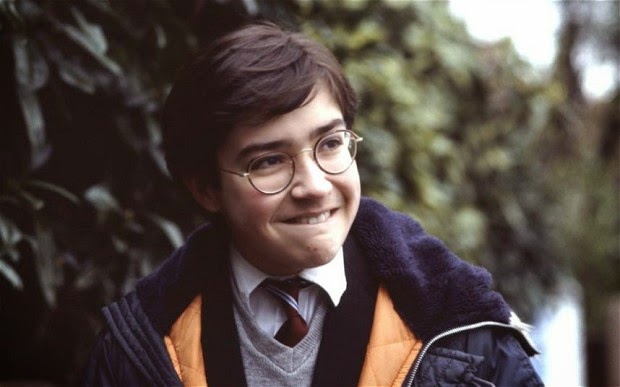

My fifteen year-old

self is lying on his bed. In front of him, spread out across the duvet, a

collection of binders and barely legible hand-written history notes. My mum

pops her head through the door: “Are you revising? Your exams are only a week

away.” She’s a teacher, so this kind of behaviour is not unexpected. Fifteen

year-old me sighs as dramatically as he can, before assuring the retreating

face that, yes, I’m getting stuck in.

As the door closes

behind her, he reaches under the canopy of school work, and extracts a

dog-eared copy of The Growing Pains of Adrian Mole. It’s been read so many

times that the binding has all but given up. The pages have been carelessly

jammed back between the covers, like a half-written manuscript in an Oxford

Don’s leather satchel. Young me looks at his watch. “I’ve got a good half-hour

before dinner; I can probably finish this and start Secret Diary again,” the

conspiratorial voice whispers inside his head. Revision will have to wait.

Adrian’s on his way to Skegness, and I can’t wait to rediscover the singular

joys of Bernard Porke and the Rio Grande Guest House.

Although there are

other books that may have moved me more; some have even changed my life; none

have maintained as constant a presence as the Adrian Mole diaries. I first met

Adrian when I was about nine. My Grandma had taken the first volume out of the

library, and enjoyed it so much, she allowed me to read it before returning it.

And although I was a few years younger than Adrian, I felt he was a kindred spirit.

Sure, he was pompous and laughably naïve, but we shared a love of the written

word, and a general air of confusion about the way that grown-ups behaved.

Whereas an older

reader might have picked up on the foreshadowing of future events, a standard

device in most epistolary novels, I shared Adrian’s innocence - although even I

could spot Mr Lucas’ intentions before Adrian did. Of course, each time I

revisited Adrian’s diaries, which was a lot in those days since there were only

two volumes to choose from, I’d pick up on more of the detail. The politics of

the time, the complex familial relationships, and the coruscating social

satire, all added fresh layers to every rereading. Adrian was the ideal

commentator on society – all seeing, if not exactly all-knowing.

Aged just 14, he

diligently reported the outcry that occurred when he accidentally delivered tabloids

to the tree-lined middle class avenues, and broadsheets to the council estate,

but expressed surprise at their response: “I don’t know why everybody went so

mad. You’d think they would enjoy reading a different paper for a change.” Neither

did it escape his notice, in True Confessions, that on the day of Andrew and

Fergie’s wedding: “I passed the Co-op where the Union Jack hung upside down,

and the Sikh temple where it was hung correctly.” Tiny moments, that spoke

loudly about the tensions of modern British life.

As the years passed,

Adrian and I both grew up, but never apart. I kept track of his first,

ill-fated move to London. I shared his heartbreak as his beloved Bianca left

him for his stepfather, Martin Muffet. And I delighted in his, albeit short-lived,

success as a TV chef. Crippling debt, appearances on reality TV talkshows and a

particularly threatening swan, all played vital roles in Adrian’s tragicomic

existence.

But, once a diarist,

always a diarist. With his maturity came a newfound awareness of politics, not

least when his fearsomely ambitious old flame Pandora Braithwaite became one of

Blair’s Babes. Even so, his unerring ability to miss the point never seemed to

fail him. Most of the time, his lack of prescience was mined for ironic humour,

but things took a dark turn in Adrian Mole and the Weapons of Mass Destruction.

Having tirelessly campaigned in support of Blair’s war, putting his unwavering

trust in the Labour leader’s integrity, he’s shocked out of his ignorance when

Robbie Stainforth, his son’s best friend, is killed in a bomb explosion in

Iraq. Adrian’s grief is palpable, reflecting a raw anger that we hadn’t encountered

before. Gone were the playful jabs at British politics; in their place, a

profound sense of betrayal.

The last time I saw

Adrian, he seemed to be on the road to recovery, following a gruelling battle

with prostate cancer. Middle-aged and once again separated from another wife,

he seemed to have finally made peace with his life. Able to set aside three

decades of unrealistic aspirations and underwhelming accomplishments, he was

looking forward to life as a grandfather, perhaps alongside Pandora – the one

that never quite got away. And that’s how I’ll chose to remember him, even

though I know he’s gone forever.

He and I were more

alike than I’d perhaps care to admit. But then, wasn’t that always the secret

of his enduring appeal? Adrian Mole truly was an everyman. Reflecting the

frustrations, obsessions and idiosyncrasies of this weird and wonderful nation.

Cataloguing its foibles with alarming precision, and yet managing to

spectacularly miss the point, more often than not. Adrian Mole; a hero in idiot’s

clothing.

No comments:

Post a Comment